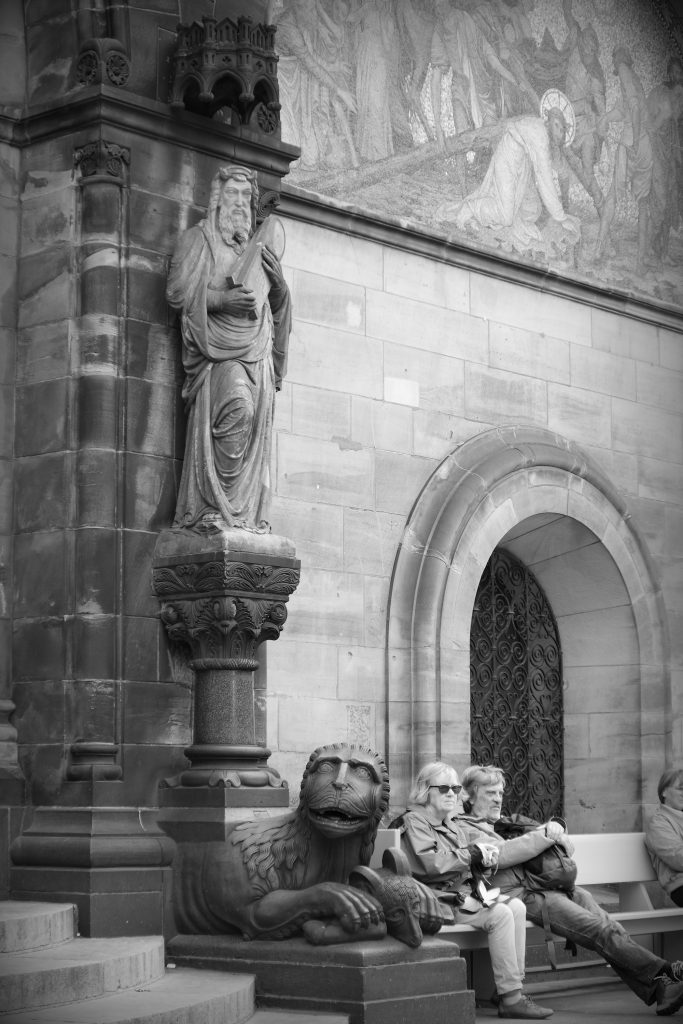

Bremen: Caught in Stone.

Welcome to fear, and friendliness. The lions in front of the Dom in Bremen are a masterwork of art and representation, even if the tale they appear to tell is not quite Bible-true and they, carved many hundreds of years ago, do not quite look like the lions we see on the Discovery Channel, or the start of old films in the cinema. They do not seem to be there to protect the church building, more as a decoration with, perhaps at the time, some hint of power, the way of life, the stories told in the Bible. We can see the lion accepting Daniel, in all probability, and perhaps even the lion which lays down with sheep and becomes a vegetarian, but also the power of the beast as it tears into a goat or a dragon, ripping their throats out, preparing them for a decidedly non-vegetarian meal, where they are the main course.

There is almost a mothering instinct portrayed here, the cradling of a single man between its paws, the protection by violence. The Church Fathers were perhaps not quite up to scratch on mythical creatures compared to real creatures, and the Here Be Dragons coupled with the lion shows how little they knew and understood of their own world, and the world outside their various lands. What they did understand, though, was the power of man, both as a violent entity, and as a creator. Those in power, symbolised by a crown or a Bishop’s hat, as both creator of the church buildings, and protector – but whether of the Church or their subjects need not be gone into further.

Equally powerful would have been the Word, and equally destructive. The Commandments brought down from the mountain, given out from a living god or, as they are received by those idolizing the golden calf, a vengeful god. In the background we see the figure of Christ, on his final journey, tormented and helped according to belief as he struggles along the route to Golgotha, toward his end. And the word of a god designed to protect and guide his children, clasped by the bearded bearer of good and bad tidings.

Ask three different people about the symbolism of the statues, especially the lions, and you’ll get three different stories. Are they protective, or vengeful? The roaring lion of Judah, or the lion which lays down peacefully with lambs? What did we have to learn in school, during Bible studies, or whichever form of learning we were expected to follow? The lion didn’t come across as strongly as it should have, when considering how well portrayed it is here in Bremen, in the different roles it played.

But we can read a story into anything we see, be it lions feasting or protecting, or mankind, resting their feet after a long day of playing the tourist. Architecture – as I mentioned elsewhere before seeking out these images – is not my thing. Symbolism, based on sparse reading and guesswork, is probably not one of my strengths either. The creatures, though, whether we understand their original meaning or not, are a part of our history, a part of our surroundings, the things which draw the tourists into our towns and cities, and provide a simple street photographer such as myself with rich pickings.